Do A&P Textbooks Have Too Much Content?

TAPP Radio Episode 94

Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Oh, that huge A&P textbook I teach from! Do I really need to cover all of it? Host Kevin Patton discusses his take on this age-old problem. Does the color of my marking pen send a signal that I don’t want to send to my students? A breakthrough in understanding how teeth sense cold. And what in the world is a tunneling nanotube—and can I get one at my local hardware store? Greek names for SARS-CoV-2 variants simplifies conversation and avoids stigma.

- 00:00 | Introduction

- 00:43 | How Do Teeth Sense Cold?

- 07:04 | Sponsored by AAA

- 08:32 | Red & Green for Student Feedback

- 18:03 | What’s a TNT?

- 23:52 | Sponsored by HAPI

- 25:06 | Greek Names for COVID Variants

- 30:24 | Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? Are Mittens Too Big?

- 36:41 | Sponsored by HAPS

- 39:15 | Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? What About Novels?

- 46:35 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

Do A&P textbooks have too much content? Don’t tell me that thought has never occurred to you! (Kevin Patton)

How Do Teeth Sense Cold?

6.5 minutes

We know that teeth damaged by caries (cavities), decay, injury, wear, etc., can be very sensitive to cold—such as ice cream or cold drinks. But we’ve struggled to come up with a mechanism for that. A new discovery proposes that the ion channel TRCP5 may be the responsible cold sensor. And that may lead to some easy fixes for cold-sensitive teeth.

- Odontoblast TRPC5 channels signal cold pain in teeth (discovery from Science Advances mentioned in this segment) my-ap.us/3w888Cg

- Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 5 (TRPC5) is a cold-transducer in the peripheral nervous system (some earlier research on the cold-sensing function of TRPC5) my-ap.us/3pnhdEM

- Image from PxHere

Sponsored by AAA

1.5 minute

A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

Red & Green for For Student Feedback

9.5 minutes

Kevin revisits his recommendation to use a green pen—not a red pen—for marking grades and giving student feedback. That holds over to digital communications, such as course announcements and instructions, too. Listen to the reasons—you may be surprised!

- No Red Pens! (Kevin’s blog post on this topic; with links to additional information/research) my-ap.us/2SbyDbr

- Give Your Course a Half Flip With a Full Twist | Episode 6 (Kevin’s earlier discussion of green pens for marking)

- Coblis—Color Blindness Simulator (you can paste in your text with color fonts, or an image, and see what it might look like in major color vision variants) my-ap.us/2T33Xt6

- Green Pens geni.us/p2BW

- Photo by animatedheaven from PxHere

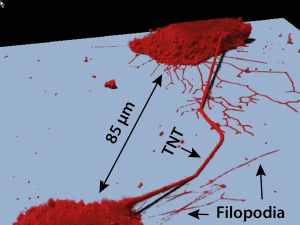

What’s a TNT?

5.5 minutes

The tunneling nanotube (TNT) is not an organelle we typically discuss in the undergrad A&P course—just like a lot of other recently-discovered organelles. But sometimes it’s worth mentioning the ongoing work of discovery in this area—and the excitement of such exploration—as a way to connect students with our course content.

- Tunneling nanotubes: Reshaping connectivity (review-opinion article mentioned in this segment) https://my-ap.us/3fUpM6X

- Wiring through tunneling nanotubes–from electrical signals to organelle transfer (an earlier work from Journal of Cell Science) https://my-ap.us/3poC5LW

- Got Proteasomes? (Kevin’s brief post about why he teaches proteasomes in A&P) https://my-ap.us/3pp0NvA

- Image from Radiation Oncology

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

1.5 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers, especially for those who already have a graduate/professional degree. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you be your best in both on-campus and remote teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Greek Names for COVID Variants

5.5 minutes

Considering the adverse social effects of calling the 1918 influenza “Spanish flu” and the SARS-CoV-2 “the China virus,” the World Health Organization has proposed calling variants of SARS-CoV-2 by letters of the Greek alphabet (alpha, beta, gamma, …) in ordinary conversation. These are to supplement the more technical systems of naming the variants in the scientific literature.

- Coronavirus variants get Greek names — but will scientists use them? | From Alpha to Omega, the labelling system aims to avoid confusion and stigmatization. (News item in Nature) my-ap.us/3uPC70F

- Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants (WHO information that includes a longer list of SARS-CoV-2 variants) my-ap.us/3vZJ0xQ

- Mid-Winter Winterizing of Our Courses | Bonus Episode 63 (where Spanish flu is discussed)

- Even More Pandemic Teaching Tips | TAPP 72 (where I apologize for using the term Spanish flu)

- Image from Wikimedia

Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? Are Mittens Too Big?

6.5 minutes

I first heard complaints about A&P textbooks being too large in the mid-1970s—when they were much smaller on average than today’s A&P textbooks. But are they really too large? Let’s explore that notion.

- Your Textbook is a Mitten, Not a Glove (Kevin’s brief article mentioned in this segment) https://my-ap.us/2E0sZP1

READ and RAID your textbook (Kevin’s brief article for students on a useful approach to using their A&P textbook) my-ap.us/2P3KuBZ - Selling your textbook? (Kevin’s brief article for students on why they need to keep their A&P textbook—to access that “extra content” in their later courses & career) my-ap.us/3g8Q9Fm

- Plaid Mittens geni.us/yicVmBi

- Photo from PxHere

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Watch for virtual town hall meetings and upcoming regional meetings!

Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? What About Novels?

7.5 minutes

Okay, novels can be too long. But only when they’re not good. Long, good novels are, um, usually pretty darn good. But we don’t dive into every detail of a novel when learning about it in a literature course, do we? What’s this got to do with A&P? Listen and find out!

- The Stranger (novella by Albert Camus) geni.us/Rwbw

- Photo from PxHere

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Kevin Patton (00:00):

Do A&P textbooks have too much content? Don’t tell me that thought has never occurred to you.

Aileen (00:11):

Welcome to A&P professor. A few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with a veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton (00:23):

In this episode, I ask, is there too much content in your A&P textbook does the color of my marking pen send a signal? How to teach since cold. What is a tunneling nanotube? And what are the Greek names of the SARS-CoV-2 strains?

How Do Teeth Sense Cold?

Kevin Patton (00:43):

There’s been a new discovery about how teeth sense the cold. I think a lot of people have had the experience of having a very unpleasant, almost painful experience of something very cold hitting their teeth if there’s been some damage to their tooth. Either through cavities, or through some kind of dental work that’s been done, or damage to the tooth. Or maybe you don’t know that your tooth is damaged. And cold ice tea, I drink ice tea all day long. So that is likely hit it, or ice cream, or anything cold can hit the teeth. And one or more of your teeth may be very cold sensitive.

Kevin Patton (01:26):

And we never really knew for sure how that worked…

I mean, the prevailing theory, as I understand it is that some scientists have proposed that there are tiny little canals in the teeth that contain fluid that moves when the temperature changes. And that makes sense, right? I mean the fluid would expand or contract as temperature changes. And that somehow, the nerves in the teeth can sense that movement and detect whether it’s contracting or moving in the direction that would happen when the tooth tissue gets cold.

Kevin Patton (02:05):

And we don’t know now that that theory is wrong, but there really isn’t any evidence to support it. I mean, it’s just like maybe it works this way. But now we have evidence, and very direct evidence that there is another mechanism that is almost certainly responsible for detecting that coldness. And it has to do with an ion channel called TRPC5. TRPC5. I love these names of ion channels. And actually, some of them are very creative. This one, it’s just another acronym. Oh well. Nobody ever asks me when they name ion channels. Maybe I should set myself up as an ion channel naming consultant and come up with really cool sounding names like carbaminohemoglobino, or something like that. But anyway, this one is called TRPC5. And it’s a molecular cold sensor in teeth they’ve recently found.

Kevin Patton (03:09):

So anyway, this is really kind of a cool story. They were not even looking at teeth. They did not set out to make this discovery. I love those kinds of stories in science. They were trying to figure out the role of this ion channel in detecting cold. And they looked for it in the skin of mammals. And they looked all over it in mice. And they couldn’t find it in the skin of mice. So they were thinking, “Well, where else in the body do we feel cold?” I think they were having lunch, I bet that was the case. They were probably having cold the drinks after work. And somebody said, “What about teeth? What about the cold sensitive teeth? Maybe that’s what’s causing that sensitivity there. Maybe it’s our ion channel that we want to study.”

Kevin Patton (04:04):

So they looked in teeth. And you know what? It was there. And that’s how this discovery was made by that kind of somewhat serendipitous thought process that this team had.

Kevin Patton (04:16):

What they found is that this ion channel is what mediates the cold sensation in teeth. Now, maybe there’s other stuff going on too, but at least this is happening there. And interesting thing that they discovered when they were trying to find out more about teeth and cold sensitivity, a really old home remedy for easing tooth aches is clove oil or different concoctions that contain clove oil. And it turns out that clove oil blocks this ion channel TRPC5. So boom, another light bulb moment of I think we’re on the right track here.

Kevin Patton (04:57):

Now of course, once we know this much, and of course there’s more testing that needs to be done, more research, more experimentation to make sure that what we think we’re seeing is what we’re seeing. What this means is there could be a target for drug therapy or some other kind of therapy that can solve that sharp pain experienced by some people in their teeth when something cold hits it. Maybe other kinds of tooth pain too. And tooth pain is horrible, and tooth pain is widely experienced. And if we can do that, especially with a simple, safe drug, then maybe this is a breakthrough.

Kevin Patton (05:41):

And I know a lot of us in our A&P class don’t really stop and cover teeth a lot, but here’s a good opportunity to link together concepts and say, “Hey, anybody experience cold sensitivity?” You’ll get some hands raised, or little hand icons pop up in your Zoom or whatever. “Yeah, I do. I do.”

Kevin Patton (06:02):

Okay. So we’re immediately making a connection with our students. We’re immediately engaging them in something that means something to them, and possibly also to their family members, and friends, and so on. So we got that going, and then we can link together this idea of tooth sensitivity to sensation in general. So now we’re linking together the nervous system and the digestive system. Who knows, maybe this sort of thing is going on in other parts of the body as well. That might be an interesting discussion and see where it goes. And of course, some of us teach A&P spent a lot of time on teeth if you’re in a program that is either in or feeds into a dentistry, or dental hygiene program, or something like that.

Kevin Patton (06:46):

So anyway, I thought it was really interesting. I can’t wait to see what’s going to happen in terms of medical applications of this. And as always, there are links in the show notes and episode page.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton (07:04):

A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy at anatomy.org. You probably know it takes both time and money getting good transcriptions for a podcast full of terms like SARS-CoV-2. And yes, my favorite, carbaminohemoglobin. [harp playing] Or even my occasional use of the Esperanto translation of carbaminohemoglobin, which is carbaminohemoglobino. Because AAA is committed to supporting anatomy education, even in the form of this eccentric podcast for A&P faculty, they were the first to step up and help out with the transcriptions, which are also used for the captioned version of each episode that’s available on YouTube or at the episode page. AAA has supported us in this way for almost four years. Isn’t that awesome? But you know what? They do so much more to help you in your A&P teaching. Go check out the American Association for Anatomy website at anatomy.org.

Red & Green for Student Feedback

Kevin Patton (08:32):

Okay. So here’s something that I first mentioned a few years ago, but I want to circle back. Because well, you may have missed it. It was way back in episode six. And also, I want to add a little bit to it. It’s a really little thing I admit. But I think it can have a big impact on the effect of our teaching on students. And that is what color pen do we use when we’re grading papers, and marking comments on papers, and lab reports, and all that stuff? When we’re sketching out things in the margin of a student’s notebook to help explain an idea.

Kevin Patton (09:10):

Well if you’re like me who began teaching near the dawn of humanity, we were all issued red pens. And that’s what we were to expect from teachers, right, is using a red pen. I mean, it stands out from whatever blue, or black, or whatever color pencil marks that they’re making on their paper. So it’s really clear who wrote what, the teacher or the student. And the comments with a red pen really do pop out.

Kevin Patton (09:44):

The problem is that our students have lived part of their life already, perhaps decades being corrected by teachers who had a red pen. And some of them have had some not so good experiences with that red pen. Not only that, but psychologists tell us that the color red is an alarming color for most people. There’s a reason why fire alarms and firetrucks are often colored in red. Because it has a certain impact on our psyche, an alarming impact. A signal of danger. [alarm sounds] Yeah. Okay. See, that’s not alarming. Is it? And red can do that to us.

Kevin Patton (10:35):

Now on the other hand, psychologists also tell us that the color green has a more positive impact on our psyche. It’s the color of nature. [nature sounds] Green is a very peaceful color, right? It signifies calm. It can signal to continue going forward, or can signal lushness, or salads, or cannabis, or minty freshness, or the green, green grass of home. Just all kinds of goodness and wholesomeness. Right?

Kevin Patton (11:17):

As I mentioned back in episode six, for a good 20 years or so now, I have avoided using a red pen. And I almost entirely use a green pen. If I accidentally pick up a red pen, which is not likely because I don’t have any red … well I might have a red pen around here somewhere? I might have my first red pen from my first teaching job or something stashed away in a box somewhere. Who knows? But usually I don’t even have red pens. But if I accidentally pick up a red pen, it’s almost like it shocks me. Like what am I doing with that red pen? And I put it down and look for my trusty green pen.

Kevin Patton (11:58):

In episode six, I said that if you run into me at a HAPS, or AAA conference, or somewhere else, sometime tap me on the shoulder and say, “Hey, can I borrow your pen for a minute?” And I will pull out a green pen. Because I always, always, always, always have a green pen with me. And you know what? At the next couple of days, the conferences that I went to after that episode came out, folks called me out on it and asked me if I had a pen handy. And you know what? None of them were disappointed. I always had my trusty green pen with me. try it sometime when you run into me in person.

Kevin Patton (12:39):

Green stands out from whatever color other people are using, especially my students. So when I’m putting grades or comments on papers, I do it in green. I think it has a little bit of positive impact. And all those little, little, little positives that we can do in our teaching I think add up, and add to the kind of atmosphere that we want to build in our course. That is an atmosphere of support, and progress, and minty freshness. And not an alarming red kind of course.

Kevin Patton (13:20):

But now that all of us are doing more and more of our interaction with students online, I also want to mention that we can carry over that minty freshness to our digital communications. I often use a color font when I want to emphasize something in a course announcement in my learning management system, or in writing feedback on a student assignment, or in emphasizing terms on a PowerPoint slide, or instructions for an online test or assignment. And I’ve seen faculty do that in a red font. Which makes sense because it does stand out and demand attention.

Kevin Patton (14:00):

But I reserve red only for items that rise to a very high level of importance. Things worth risking the possibility of triggering an alarm reaction. Something has to be of code red urgency for me to use a red font with students.

Kevin Patton (14:20):

What’s my go-to color? You guessed it. Purple. No, no, no. It’s green. Of course it’s green. I’ve found that works really well for both analog and digital communications with students. But I guess purple is okay too, if that’s what works for you. I’m not recommending green as the only choice. What I’m recommend is that it’s worth it to be intentional about the colors we use in communicating with students. Because we may be unconsciously sending some unintentional signal with the colors we use.

Kevin Patton (15:00):

But wait. You might be thinking, “What about being conscious of the experience of students with atypical color vision? Won’t using green for student feedback mess them up a bit?” Well, that’s a great question. That’s a really great question. If that thought did occur to you, you get a gold star. I mean a green star. Green star for you. That means that your default mode of thinking as a teacher includes inclusiveness.

Kevin Patton (15:37):

One of my goals as a teacher is to be more inclusive and become more aware of potential roadblocks to learning for all of my students. But I don’t think my use of a green pen raises any red flags. Do you see what I did there? Red flags? Okay. You should be used to that by now if you’re a regular listener.

Kevin Patton (16:01):

Okay. So first, I mainly use the green pen for feedback. So choosing any one color and sticking with it shouldn’t be a problem for almost any kind of visual issue, including color discrimination. Even where discrimination is important, such as using green to highlight terms in a PowerPoint slide or to emphasize a phrase within an announcement, shouldn’t be a problem if the contrast is good. And if I use a secondary method along with the color. And what I mean by secondary method is also use boldface, or underline, or something like that.

Kevin Patton (16:40):

But even in those cases, when I put red and green highlights within black text into one of those online filters that represent atypical color vision, the green still works just fine. So I’ve tested that at least the best way I know how. To see, is green going to mess up my students with atypical color vision? And you know what? In some cases, it looks even better than using red. So maybe if that’s your only basis for choosing a color of what it’s going to do with your students who have atypical color vision, then maybe green is a better choice than the usual more commonly used red. So I still haven’t found a good reason to give up my green pen, and I still have a partial case of it in my cabinet. So there’s that incentive to keep using green pens too.

Kevin Patton (17:35):

One last comment on this. I don’t use a red pen when I’m writing notes or comments when doing peer review of teaching by my colleagues. Nor in those ubiquitous feedback forms at the end of workshop sessions. I want to support my colleagues, not alarm them.

What’s a TNT?

Kevin Patton (17:57):

I think some of us that teach A&P very early in the course spend at least some time reviewing some of the basic organelles that we know are going to come up in the story of the human body next semester or two. So we’re going to be looking at things like mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum, and lysosomes, and Golgi apparatus, and all kinds of those things. To students, it seems like an unmanageably long list. But when you look at the number of organelles that science knows about in cells, it’s a very, very, very short list.

Kevin Patton (18:40):

So I want to emphasize that to my students. I want them to know that there are additional organelles. And a couple of those organelles I go into that a lot of A&P teachers don’t go into like the proteasome, because I think that really helps explain the whole process of how cells make and handle proteins within the cell. And that’s important in a lot of disease mechanisms as well. So I cover that one. And then there’s a handful of others that I probably don’t need to cover, but I mention them just to give them examples that, “Well here’s a funky looking thing, and here’s what it does. And you don’t need to remember that, but I want you to know that there are many other organelles. And believe it or not, you’re looking at the short list in this course. And you know what? We’re learning about new organelles all the time.”

Kevin Patton (19:34):

And I just ran across a recent paper as a review that is called tunneling nanotubes, reshaping connectivity. And it’s all about tunneling nanotubes, which are often abbreviated TNT. Wow. That’s kind of an interesting analogy. After having seen all those Road Runner cartoons, TNT means something completely different to me. So I’m going to have to get over that if I start to end up mentioning this in my course.

Kevin Patton (20:06):

But tunneling nanotubes are actually very simple kind of organelle. They’re usually described as open-ended channels that sort of connect plasma membranes that is form a kind of membrane continuity between cells at either end of that tunneling nanotube.

Kevin Patton (20:28):

So in other words, picture two cells. Picture a really long, thin hollow tube in between them that’s made of membrane. So functionally, they’re kind of one cell. and things can move back and forth along that tube. So one cell can communicate in a very direct way and very rapidly if need be with that other cell. So it can be different kinds of signals. Either signals to do something or signals to something. Could be signals to destroy yourself or something like that, all kinds of possibilities. And we’re just learning about these. I mean, we’ve been learning about them for a few years, but still in the very early stages. And that’s kind of the point of this review article, which I’m not going to go into all the details. It’s really a very fascinating read. And I think that my appreciation for my understanding of cell biology has improved greatly because of this. I look at the other organelles differently than I did before.

Kevin Patton (21:32):

For example, think about how nerve extensions like axons are made. They’re made it turns out just like these TNTs, these tunneling nanotubes. And it may be, they proposed this in the paper, maybe this is how the nervous system forms, at least in the brain and how brain tissue. Maybe cells, neurons, developing neurons connect with each other in the very early developing one of the brain with these tunneling nanotubes. And then eventually, those are replaced by synapses. So maybe when I describe picture a tunneling nanotube like a long axon, maybe there’s more to that than just being an analogy, right? Maybe they’re part of that same process. Maybe axons really are tumbling nanotubes that don’t quite make it to connect up entirely with that post-synaptic cell. And if that doesn’t actually happen in embryonic development of the brain, then maybe evolutionarily it preceded the formation of a synapse based network in brains.

Kevin Patton (22:55):

So there’s that and there’s, oh my gosh, just all kinds of other aspects to this. But my point is, is that I don’t know, I’m kind of excited about learning or about tunneling magnitudes. And you might be excited too, maybe not. Just try it and see. I know it sounds kind of wonky, but go ahead and try it and see and read it, and see if you’re excited. And see what kind of insights it gives you in about other parts of the cell.

Kevin Patton (23:24):

But also, that excitement, I want to carry that over to my students. I want to tell them, “Hey, there’s some exciting things that we’re discovering about cells, and all these new organelles that are being discovered, and organelles that are being proposed and what we’re learning about them.” And that kind of engagement, and enthusiasm, and excitement I think really helps learning. So there you have it.

Sponsored by HAPI

Kevin Patton (23:52):

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the master of science in human anatomy and physiology instruction. The HAPI degree. As you may know, I’m on the faculty of this program, and we’re getting set for the capstone teaching practicum that we hold at the end of each summer, followed by the commencement. I volunteer for this part of the process because well, I’m selfish. Yeah, really. I just love that rush I get when I see both experienced and new A&P faculty demonstrate the progress they’ve made in both the art and the science of teaching, as well as an increased depth and breadth of understanding of concepts of A&P. And well, I learned so much myself during the practicum. Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/hapi, that’s H-A-P-I. Or click the link in the show notes or episode page. There’s a new cohort forming right now. So yeah, now’s the best time to find out more.

Greek Names for COVID Variants

Kevin Patton (25:07):

If you’ve been listening to this podcast for long enough, you may remember that before this COVID pandemic started, I had an episode about how to be prepared as an instructor just in case our colleges, or even just in our course, we want to implement some health safety strategies related to infectious disease, such as viral outbreaks.

Kevin Patton (25:33):

Now at the time, I was thinking about influenza outbreaks mainly. But I did mention there’s this other virus on the other side of the world that could become dangerous. We might have to react to it. Maybe we’re going to have to close down a school or two, or at least take some health precautions in that. And I told the story of how what I was calling the Spanish influenza outbreak of 1918 played out in St. Louis, and how social distancing, which I explained what that was because that was the term that most people didn’t know. But yes, there was a time not so long ago when people didn’t know what the term social distancing meant. And talk about how wonderfully it worked in my hometown of St. Louis compared to other major cities that did not implement the strict social distancing that St. Louis did during that 1918 influenza outbreak.

Kevin Patton (26:30):

And notice that this time, I called it 1918 influenza outbreak instead of the Spanish flu or the Spanish influenza outbreak. And that’s because we are trying to get away from that as a society of scientists. We’re trying to get away from naming diseases after localities. Because look what happened with COVID, which some people have called the China virus. And look how that has played out in the social context. Look how that has adversely affected people of Asian descent, especially Chinese, but all Asians.

Kevin Patton (27:07):

And that is not good. That is not what we as a scientific community want to be about. And it wasn’t intentional that we had these names like Spanish flu and so on, but that harmed people too. I don’t remember 1918. I wasn’t around in 1918, but the records show that it really did cause some discrimination against people of Spanish descent, and against the nation of Spain in political contexts even. And we don’t want to do that in science. We don’t want to be part of that or instigate that, unwittingly or not.

Kevin Patton (27:41):

So there’s been a recent development in this that I want to mention. At the end of May, 2021, the World Health Organization announced that the variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused COVID-19, those variants are now going to also have the designation of Greek letters. Alpha, beta, gamma, delta. That’s what I mean by Greek letters.

Kevin Patton (28:13):

Now there’s already some scientific nomenclature that can be used in describing these variants. For example, the one that in the news is often called the UK variant, that one goes by the designation of B.1.1.7. There are a couple of other systems of nomenclature that you can use, but they’re all about that easy to use. B.1.1.7. Or the South Africa variant would be B.1.351, and yeah, people aren’t going to use that in ordinary language. And certainly not when you’re reading the news or reporting the news. And for those of us that teach, if we’re going to talk about COVID at all, we’re not going to say, “The B.1.1.7 variant does this, and the B.1.351 they discovered that in South Africa.” No, no, no, no. We’re going to use the UK variant, the South African variant, the Brazil variant, the India variant, and so on. But there’s this potential for it having these undesirable consequences.

Kevin Patton (29:21):

So the World Health Organization said let’s develop this additional kind of nomenclature that anybody can use and everybody is familiar with. That is alpha, beta, gamma. So alpha is the UK variant, or a synonym for the UK variant. Beta or the beta variant is the synonym for the South Africa variant. And that Brazil strain, that’s called gamma. And the India strain, that’s called delta. And we can add to that list as we discover and confirm the discovery of new variants.

Kevin Patton (29:58):

So I want to adopt that. Because I don’t want to be part of any kind of accidental diminishing of people from South Africa, or people from Brazil, or India, or the United Kingdom based on that. So I have a link to it in the show notes and episode page.

Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? Are Mittens Too Big?

Kevin Patton (30:24):

Do A&P textbooks have too much content? Don’t tell me that thought has never occurred to you. One of my first experiences with AP textbooks was when I was a very young student hanging out in the bio lab, and a couple of faculty were off to the side discussing which book to adopt for the new A&P course they were developing. Of course, that turned out to be the A&P course that I took as a student.

Kevin Patton (30:55):

They were lamenting that all their choices had way more content than they felt should be covered in the course. Well, that was in the mid 1970s. I told you I was a very young student then. It was a topic of conversation then, and you know what? It still is today. But I was just a beginning student back then. Now I’m a seasoned A&P professor. And as it turns out, a veteran A&P textbook author.

Kevin Patton (31:31):

Back then in my youth, I didn’t really have an opinion. And if I had, it would not have been an informed opinion. Now, I not only have an opinion. I have an informed opinion.

Kevin Patton (31:49):

Now you know that I usually don’t focus on my role as an A&P textbook author in this podcast. And I’m not really going to focus on it now, except to say that I not only have an insider’s perspective on A&P textbooks. I’m somewhat of a student of what can make a textbook useful for learning, how best to use textbooks and course design, and what doesn’t work very well when using a textbook.

Kevin Patton (32:20):

I mean, I actually do both guided and unguided learning activities exploring those topics. But I’m also bringing up my role as a textbook author to be transparent about my biases in favor of textbooks. I think A&P textbooks when used wisely by faculty and students can be incredibly valuable tools. I don’t think that learning in an A&P course benefits by minimizing or skipping the use of a good quality A&P textbook. The trick for effective learning with a textbook in my opinion is understanding that most A&P textbooks are not intended to have students learn all the content.

Kevin Patton (33:11):

Back in 2014, I wrote an article in which I used the analogy of mittens to describe how textbook content fits the typical A&P course. In that article, I stated that textbooks fit like a mitten, not a glove. Because the best they can do is approximately fit course objectives and content, student learning needs. And well, your teaching approach.

Kevin Patton (33:42):

But mittens are great. They cover your hand, and they give you some wiggle room. As a mitten, your course textbook should cover what you need it to cover. It’s okay if it covers a bit more than you need. That extra coverage will be used later for reference, and future learning in clinical courses, long after a student leaves your A&P course.

Kevin Patton (34:14):

Extra content also helps fill in prior learning gaps, which allows students to get it on their own as they read a chapter. Or as they rate a chapter for specific information needed during their study, or to answer a case study or other active learning assignment. Or to figure out what went wrong on their first attempt of a test.

Kevin Patton (34:42):

And that extra content may help students better see the context and the importance of their required content. And well, satisfying natural curiosity with a bit more content than they’ll see on a test or exam is not exactly a bad thing either.

Kevin Patton (35:07):

Although well-fitting mittens cover a bit more than they need to, a mitten really shouldn’t be too big. So having so much content in a textbook that it’s hard to stay focused mainly on the required content is not good for learning. Conversely, a mitten should not be so small, that you can’t get it around your big hand or wiggle your fingers around a little bit. That wiggle room is important. That’s because the fit will change as you and your course evolve. As you gain teaching skills, as you adjust your techniques, as you adopt new strategies, and as your students’ needs change.

Kevin Patton (35:54):

The key is to think of a textbook as an off the shelf item that will never fit precisely. It’s up to you to make sure it fits well enough. And the only way to get that fit is to try on all the mittens. Don’t just glance at them, really put your hand in it, and wiggle it around, and see what they’re like. Plaid mittens, they’re the best. That has nothing to do with the analogy I’m making here. I just like plaid mittens. You know what? Let’s take a quick brain break, and I’ll be back with more on this topic.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton (36:41):

Marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. For those of you who just participated in the 2021 annual conference, you may remember that emotional moment when the HAPS president’s medal for this year was announced by Wendy Riggs, who is our current president. As usual, when I heard the name of the recipient, I said to myself, “Well yeah, of course.” Because the HAPS presidents have done a great job in selecting folks that have done truly great service for A&P teachers, and are generally just great people too.

Kevin Patton (37:29):

And this year’s winner is a winner on both counts. A real servant to the A&P teaching and learning community, and a wonderful person besides. It’s my long friend, Judi Nath. You may know her as a textbook author in both A&P and medical terminology or as a long time leader in HAPS, which she wears a lot of other service hats too. If you’ve ever had any kind of interaction with Judy, you know that she’s a warm and delightful person who’s ready to support you any way she can. The kind of person who brings a smile to your face when you hear her name.

Kevin Patton (38:14):

Not only has she helped me personally in several ways over the years. But get this. Within hours, or maybe it was minutes after receiving the HAPS president’s medal, Judi stepped up once again. This time to help form and coordinate a discussion group of A&P textbook authors to help us help each other grow in being more inclusive in our writing. So cheers to you Judi, [glasses clink] for getting this prestigious award and for not resting on your laurels. By the way, I’m sure she wouldn’t mind you sending her a note of congratulations. To look up Judi Nath’s contact information or find out more about HAPS, go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S.

Are A&P Textbooks Too Long? What About Novels?

Kevin Patton (39:15):

Besides the mitten analogy, I have another analogy that I like to use that gets at that discomfort that all of us have some times about whether our textbook has too much information in it. This analogy compares our A&P textbook to one of those novels, or novellas, or full length plays or whatever that we were assigned for reading and our undergraduate literature classes. In lit classes, students need to read the whole thing or pretty much the whole thing to get a good feel for the story. But the teacher selects which characters, which themes, which events and so on to focus on to build an understanding of the essence of the novel. It’s not at all unusual for lit professors to adopt novels from their department’s required list. Or if not that, from a widely recognized cannon of novels for a particular kind of lit course like I don’t know, modern British literature, or contemporary American literature. Or whatever, the literature of A&P. I don’t know, whatever kind of lit course they’re teaching.

Kevin Patton (40:30):

But let’s talk about I don’t know, that imaginary one very popular novel used in a bunch of freshman lit classes. One lit professor might choose different things to have their students consider and focus on than that other professor that is assigned the very same novel. But in each course, the students still get a good understanding of that novel.

Kevin Patton (40:57):

In my early lit course, I probably walked away with a different understanding of Albert Camus’s novella The Stranger than you did. Because we had different professors who chose to have us focus on and think about different aspects of that novel. But we both walked away with an overall foundation of knowledge about that book. We can take that learning further if needed. I never did take any additional courses about the works of Camus, but I did read another of his novels, which actually I liked better than the first one. Because I was intrigued by his storytelling and weird perspectives. And I’ve run across occasional references to his works and other reading or learning that I’ve done. But I could have dived even deeper into Camus. You know why? Because I had a good start in that freshman lit class.

Kevin Patton (41:58):

I think the textbook we use in our A&P course is like that novel or novella used in a literature course. There’s more there than we need for our particular course or for these particular semesters. We can use some of those deeper parts a different semester. Or a student can use those other parts to add context, and satisfy questions, and get a deeper or broader understanding of the overarching story of the human body.

Kevin Patton (42:34):

Like a lit teacher, any A&P instructor may choose to change the focus from one semester to the next. For example, as their own depth of understanding of the story of the body changes. And don’t say that doesn’t happen. That still happens to me after decades of teaching A&P. I’m always having light bulb moments in class as I discuss something with students, or give a mini lecture on it, or help a student work out a case study or something like that. A light bulb goes off and say, “Oh my gosh, I never really saw that connection before. I never really understood that what’s going on here is the same kind of thing that’s going on over there.” My understanding of A&P gets deeper and broader every single year, even after all these years.

Kevin Patton (43:26):

So yeah, I’m going to change my focus sometimes as my understanding changes over time. And also is my understanding of how students can benefit from the story. I might make some realization that if I focus on this instead of focusing on that, students get a much better idea of what’s going on.

Kevin Patton (43:46):

So as I make those discoveries, while I’m practicing my teaching in the classroom, then that’s going to change how I’m going to teach it next semester or the next time I teach that course. And like a lit teacher, there may be a few extra facts, or stories, or history that we want to bring into our course. Things that aren’t there in the novel, I mean textbook, that we think our students will benefit from knowing about or discussing. Could be current events. Could be social context. That’s very important these days I think in education.

Kevin Patton (44:26):

In case you need to hear this today, yes, you have permission to select which bits of content you want to from the textbook to meet your course objectives. No student will learn all of it in one or two semesters. No matter how much you insist that they learn all of it, it’s not going to happen. And no matter how many tricks you use, it’s not going to happen. We’re just relying on them picking up the parts they need over the next few courses in the first few years out in the field.

Kevin Patton (45:05):

And you know what? They will. They’ll pick up that extra information that you couldn’t get into their heads during the one or two semesters you had with them. They will pick that up. They always do. Remember, real learning requires cycles of forgetting and relearning anyway.

Kevin Patton (45:27):

By the way, A&P textbooks really do have a vision and a story to tell, with a particular style and subtleties that inform and support. Even if they’re not readily apparent in a quick casual read, or the usual flipping through a few pages that many of us often do when we see a different A&P textbook than we’re used to using. But if we look for the vision and the story of each A&P textbook, they will reveal themselves. Or ask the authors, they’ll be glad to talk to you about their vision of their A&P textbook and the story they’re trying to tell in their A&P textbook.

Kevin Patton (46:14):

I think it’s our individual responsibility as educators to choose wisely. A good textbook is big enough to allow a variety of choices that individual instructors may make in their courses in different semesters.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton (46:35):

There’s a lot of stuff I talked about in this episode. Stuff you probably want to discuss further. Well, why not share this episode with a colleague and get that conversation going? Here’s an easy way to share this episode. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/refer to get a personalized share link that will not only get your friend all set up in a podcast player of their choice. It’ll also get you on your way to earning a cash reward. I always provide links if you’d like to dive deeper, or to check my facts. If you don’t see links where you’re listening right now, go to the show notes at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/94. And while you’re there, you can claim your digital credential for listening to this episode. And please send comments, questions, or content contributions to the podcast hotline. That’s 1-833-LION-DEN or 1-833-546-6336. Or send a recording or written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. Hey, maybe I’ll see you soon in my private A&P teaching community, theAPprofessor.org/community. If not, well, I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen (48:07):

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton (48:20):

Apply the contents of this episode to all infested areas.

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is with the free mobile app:

Or wherever you listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

![]() Please click the orange share button at the bottom left corner of the screen to share this page!

Please click the orange share button at the bottom left corner of the screen to share this page!

Kevin's bestselling book!

Available in paperback

Download a digital copy

Please share with your colleagues!

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)