Power Tips for Dissection Activities

TAPP Radio Ep. 34 TRANSCRIPT

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the LISTEN button provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association of Anatomists.

I’m a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Episode 34 Transcript

Power Tips for Dissection Activities

Introduction

Kevin Patton: My mentor, Sister Virginia Brinks, used to say, “Students often don’t realize that they are their own best teacher.”

Aileen: Welcome to The A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching Human Anatomy and Physiology, with host, Kevin Patton.

Summer neuroscience workshop

Kevin Patton: In this episode, I discuss a Summer Neuroscience Workshop, I discuss ganglion cells in the retina, and I talk about some ways we can make dissection activities a lot more efficient. I want to tell you about a Neuroscience Workshop that’s coming up in the summer of 2019. Specifically, it’s a one-week workshop in July, from July 14th through the 20th, and it’s at the University of Missouri in Columbia, otherwise known as Mizzou, which is in the heart of the State of Missouri, and it’s funded by the National Science Foundation. This is, I think the 13th offering of this workshop, and I went to the first or second one, and I really enjoyed it. One of the unique things about it is it’s offered by a team made up of engineering professors and biology professors, so you get to take kind of an engineering look at how neurons, and action potentials are modeled, and neural pathways are modeled.

Kevin Patton: Sounds complicated, but it’s really very interesting, and it’s targeted to undergraduate faculty from the biological sciences, from psychology, physics, math, engineering, anyone who has an interest in teaching and learning more about neuroscience. One of the other great aspects of it, besides it just being a great workshop is that it’s funded by the National Science Foundation, and that not only covers the workshop itself, but there’s funding available for lodging and for meals, and depending on what the expenses are, there may be some grant money available for travel as well. The downside is there’s only room for 10 participants, so you got to get in there early. I have a link in the show notes and at the episode page at theapprofessor.org to more details if you’re interested, and even if you can’t make it this year or you’re listening to this episode after it’s too late. By the way, the deadline for applying is February 15th, so if it’s after that time or just doesn’t work out, or July of 2019, hopefully they’ll be doing this again in future years, so you’re going to want to get on their mailing list and tell them that Kevin Patton sent you.

Kevin Patton: Maybe that’ll … I don’t know if that’ll get you moved up or moved down on the list, but you can try it and see. Anyway, if you’re listening to this on the app, I’ll have a PDF on the app, so that might be a little handier than going to the link that I’m going to give you. I hope some of you go, and if any of my listeners go, please do report back on the podcast hotline what you learned and what you gained from it.

Ganglion cells

Kevin Patton:

You may have heard some news recently about some breakthroughs that have been made in understanding specialized cells in the eye that link to the mood regions in the brain, especially those connected to what is sometimes called Seasonal Affective Disorder or Winter Depression, and it turns out that that’s really just the latest step we’ve made in progress that has been going on actually for decades, and it relates to sort of a second kind of vision, besides the vision that forms images that we normally think of when we think of vision.

Kevin Patton: There is a second kind of vision which doesn’t form images, but instead, is detecting changes in daylight throughout the day. That helps our circadian rhythms and our body clocks in general sort of synchronized to our environment and understand not only what time of day it is, but what time of a lunar month that is, and what time of the year it is that is what season it is by detecting changes in the amount of reflected sunlight available at night from the moon, so there’s our lunar cycle, and the amount of direct daylight, direct sunlight that gets to us that changes in duration from one season to another, and maybe … I’m actually recording this on the day of the winter solstice, so that kind of plays into our awareness of this calendar of the seasonality of daylight length. I just want to go back and maybe emphasize that it might be worth our while at least in a two-semester A&P course where we have a little bit more time to dive a little more deeply into things, to really mention that role of the retinal cells that deal with that sort of vision. I think all of us, no matter what level of A&P we’re teaching at in an undergraduate course, I think we all cover rods and cones and what their general function is, even in a very cursory way that we just have to do to fit everything into an A&P course, but I wonder how many of us go into the ganglion cells.

Featured topic 1: Dissection lists

Kevin Patton: Now, you may recall that the ganglion cells are in the retina, and the light actually hits them before it hits the rods and cones. They do receive input from the rods and cones, and for a long time, were thought to be solely a part of that network of information that is coming from rods and cones, and is eventually being relayed to the brain for further processing, but it turns out that at least some of those ganglion cells contain a visual pigment of their own. Not the same visual pigment that is in the rods and cones that is rhodopsin in the rods and various forms of photopsin in the cones, but it has melanopsin. Melanopsin is sensitive in a wide range of blue colors, and so that’s why you often hear about a blue light imitating daylight so much, and when we’re looking at screen devices for example, during the time when our environment really should be dark, that is without sunlight, if we’re watching things that have bright blues of the right combination of blue wavelengths that can fool our ganglion cells, and therefore, our brain into thinking that the sun is still out, that can really mess up our circadian rhythms. There’s all kinds of filters and even built-in software that can change it to a less blue light. It makes everything look kind of orangeish when you start removing the blues, but a lot of people really get a beneficial effect in terms of preserving their natural circadian and seasonal rhythms.

Kevin Patton: Some of this newer research is sort of a step in the right direction, and for quite a while, we’ve known that the ganglion cells are sending some of their information to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, that’s a nucleus in the hypothalamus that is just above the optic chiasma, and then, it’s routed from there to the paraventricular nucleus, which is nearby, also in the hypothalamus, and then there’s all kinds of convoluted pathways that have been proposed, and some of them have actually been shown to occur, maybe even going down into the superior cervical ganglion and back up again, and sometimes it goes to the pineal body and we’re just now kind of working out where all of this goes, and we know the pineal body or pineal gland is going to be secreting melatonin in different levels as that blue light level changes throughout the day, and so some of it’s been worked out, but there’s a lot more to workout, and there’s a lot more to work out in terms of what the brain is actually doing with that information, so some of it, we know about in terms of the release of melatonin. As we work out all the different things melatonin might be doing throughout our body in terms of synchronizing our body clock mechanisms, we’re also working out other places in the brain that might be processing that information, so that’s kind of what’s new. Even though we’ve known about a lot of this for a long time, it’s only recently that we’ve started to really apply this in our practical day-to-day living, and now, we can give the anatomy and physiology behind that. Not only that, impart to our students that, “Hey, this is ongoing science. We still don’t have it completely worked out.”

Kevin Patton: “There might be some new wonderful things that we can learn that is going to make these daily practices even more effective in terms of preserving a natural and healthy kind of circadian rhythm in terms of at least the light information that’s coming into us.” I think it blows students’ minds a little bit when they understand that there’s another kind of vision that we are detecting light for other reasons, other than visualizing our surroundings. That’s kind of fun to weave into your course, even if you’re not going to make your students responsible for that information. At least there’s some stories that we can weave in there that are going to help motivate our students and help them see the practical applications of what they’re learning in their A&P course.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

This podcast is sponsored by HAPS, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years.

Kevin Patton: Go visit HAPS at theapprofessor.org/haps. Over the years that I’ve been teaching anatomy and physiology, I’ve found that when I do a dissection activity in the undergraduate A&P lab course, it can either be a real, big mess that ends up being a waste of time for students, where they’re not really learning much of anything outside of what we could have otherwise learned in the lecture course, but it can also be a very focused activity that is not only interesting and motivating for students, it also helps them learn structures in a deeper, more thorough way. A tool I’ve found that’s very helpful in getting it to that latter form, that is a more focused kind of lab activity, is what I call a Dissection List. You might have another name for it. It’s really just kind of a version of a generic lab list, that is a list of all the structures that a student must identify in a dissection.

Kevin Patton: It will include all of the structures that a student must find and all of the structures that a student must be able to identify when they get to the lab practical test, and that could be different. I have had dissection activities where I’ve given them a list of structures to find, but then marked off only a subset of those that I know I want to test them on, so those are the ones they need to keep practicing. Not just find it, but get to know it thoroughly. Really, it’s sort of a form of a set of learning outcomes. In other words, what you need to be able to do at the end is identify this list of structures.

Kevin Patton: That’s our dissection list. Honestly, I thought everybody did this in A&P lab, because when I first started teaching A&P, all those many years ago, I was the second of two A&P professors hired at our college. The A&P teacher who had been there for many years before me had been teaching A&P for, I think a little over 50 years, or maybe it was a little less than 50 years. I don’t know, or maybe it was 150 years. I just remember thinking she was really old.

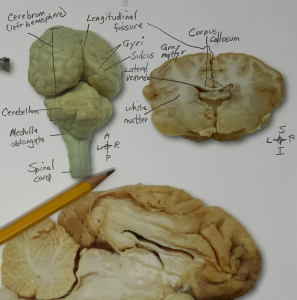

Kevin Patton: Of course, I was really young at the time, so of course I thought she was really old, but she was pretty old, but she was also very wise. One of the first things she did in mentoring me was to hand me her lists of dissections. She’d say, “Here’s the sheep brain dissection, and here’s the sheep heart dissection list. This is what I use. You can use it, or you can adapt it, but here it is.”

Kevin Patton: She was a great mentor. I learned so much from her, and I just thought, “Well, that’s the way everybody does it”, and I do know that a lot of people do it. Maybe a lot of you listening use a dissection list, but over time, as I’ve interacted with more and more other A&P teachers, I’ve discovered that many A&P teachers do not use a lab list of any kind, and certainly not a dissection list. Even if you’re one of those that does use a dissection list, listen along for two reasons. One is, there may be something that strikes you in my description of this in how it’s used that might help you make your list work better, or something might strike you that, “Hey, he didn’t cover this, and I found this aspect of a dissection list to be really useful.”

Kevin Patton: Great. Then, you can call in and share it with the rest of us so we can all learn from what you’ve found. Let’s get into it. Let’s look at the list itself. There’s all kinds of formats and options in terms of how you put together the list. It can be literally just a list format. Maybe bullet points, maybe organized in a way where you’ll have like sections, and then indented bullet points under that, so let’s say one region of the brain, and then bullet points under that, another region of the brain bullet points under that.

Kevin Patton: By the way, before I get any further, I am referring to dissections of small specimens, not of the whole human body that’s going to take the entire semester to do. Although, this can be adapted for that kind of use too. I’m talking more about discrete single organ dissections like a sheep brain, a sheep heart, a spinal cord, an eye, a mammalian eye or something like that. It could be a bulleted list as I mentioned. I’ve also seen people do lab lists in a table format, so it’s still kind of a list, but it’s not strictly a list.

Kevin Patton: It’s a list in the form of a table. I’m sure that there are other kinds of formats that work, but those are the two, either the traditional list or a list in the form of a table that I’ve seen used. One of the things that you might want to put in the list is for each structure that is listed there, each structure that a student must be able to identify, I might also somehow indicate there either as a different column in a table or as maybe a little symbol with a footnote or a parenthetic remark, which specimen the student must be able to identify it on. Now sometimes, we use more than one specimen, like I might have a slices from a human brain or we might have an actual human brain that students can look at, along with working on their own individual sheep brain, so I might mark on the list, “Well, which of these structures do you need to be able to identify in the human specimen, and which do you need to be able to identify in the sheep brain specimen?”, or maybe it’s not a dissection specimen that goes along with, let’s say the sheep brain. Maybe it’s a model of a human brain or a chart of the human brain, or maybe I want them to be able to identify it in photographs.

Kevin Patton: I want to tell my students ahead of time that sort of thing like, “How are they going to be tested? When they get to the lab practical, is it just going to be sheep brains or are they going to have to be able to pick things out on a model, on a chart? Is it all going to be sheep brains or am I going to have human brains in those charts and models and so on?” Another thing I might want to mark on there if it makes a difference is, “What is the view that the student needs to be looking at the structure when they are going to be tested on that dissection?” For example in the sheep brain, I might list a particular structure and I might mark that they need to be able to identify it in a midsagittal section, or maybe a midsagittal section and in a [frontal 00:18:44] section, or is it in an internal aspect or an external aspect of a structure?

Kevin Patton: You want to think through those things because if students are studying it one way, not realizing there’s another view, there’s another angle at which they could get to a structure, they might not be well-prepared, and our goal is not to try and trick students, right? Our goal is to try and set them up for success so that they really are very thorough in their studying and in their practicing. Another option for that lab list for that dissection list, and I love this option and a lot of people don’t think to do this is don’t just put bullet points, use check boxes, tick boxes so that the student can tick off or check off what they found as they find them. I’ve also toyed around with having two columns of check boxes. One is, “Did you find it?”, the next one is, “Do you feel fairly confident about it”, that you’re really certain that you can find it again.

Kevin Patton: It kind of forces them to not only make sure they found everything because they’re checking it off, and as you’re walking around the room and helping them, you can check their checklist and see, “Well, have you found a lot of these? Are there missing things that haven’t been checked and maybe keep an eye out for people just kind of boom, boom, boom, going through, checking off things without even looking at their specimen?” It does help them keep track, but by having that second column or that second set of check boxes, it also, at least it’s our attempt to push them into stopping for a second and thinking it through, “Do I really know this, or am I going to leave that unchecked for later?” It’s sort of a certain confidence level. Of course, they will not have mastered it completely because they’re going to have to come back to that multiple times with some space in between before they really have it mastered, so they’re going to have to do some studying outside of lab, but there is a certain level of confidence that they can get to within the lab, or maybe you can tell them, “Well, just don’t check that second column off while you’re here. Don’t do that until later in your study when you really feel like you’ve mastered it.”

Kevin Patton: I’ve also seen dissection lists that leave a little space for notes so students can take some notes, write on that list, so that now it becomes not just a tool for guiding them for what their learning outcomes are, but it’s also a tool for them to take notes for themselves. I’ve also heard of people leaving spaces for little sketches in there, like you might do maybe sketches. Sometimes you’ll see this in lab manuals for in the lab report or histology or some other microscopic exploration, where there’ll be like little circles or little squares where the students are asked to sketch out what they see under the microscope. We can do that in dissections too where they sketch out the different regions of the sheep brain, for example and so on individually there. Now, that can get kind of big and unwieldy for a list, so you can take it or leave it, see what works best for your style of teaching and the style of learning that your students are using, but it’s a thought.

Kevin Patton: You might also want to include maybe special notes or annotations with the different structures in the list. For example, you might want to make a note that this may not be present in your specimen, because like for sheep brains, depending on how they’re prepared, how they’re taken from the sheep for example, you may not see many if any of the stubs left from the cranial nerves. You might not see the hypothesis. You might not see anyone of a number of different structures, so you might want to make note of that on the list like, “Well, yeah, here’s the master list, but here’s some things that you might not see in your specimen”, or you might have to look around to several specimens defined one where this actually exist because they’re not always easy to find, or you might make a notation like you might want to ask for help with this one. “Call me over when it’s time to look for this one because this one’s tricky”, or you might want to make a note with a structure that says, “This one is only visible after you’ve moved this other structure out of the way or after you’ve lifted up out of the way or push it out of the way or whatever.”

Kevin Patton: Another thing about these dissection lists that’s very important is they need to be organized logically. It’s only minimally helpful if you’re listing the structures alphabetically, because then, as students progress in a logical way through their dissection, looking at one region, then another, then another of the specimen, they’re going to be hunting all over the place, but if you group things logically, not only is that going to help them find the structures on the list as they’re doing the dissection, it’s also going to provide a graphic organizer for students to begin to build their conceptual framework of what this whole big set of structures is. It helps them see how different structures are related to one another by organizing your list in a logical manner, that is an anatomically logical manner. Since we’re on the topic of organization, I also want to strongly encourage you to check it again, and then put it away, and then check it again before you use it, because we want to have perfect spelling and perfect formatting of terms so that students are learning the exact correct terminology. I see a lot of lab lists that have a lot of typos, a lot of just plain old spelling errors in it, a lot of formatting errors where things are improperly capitalized, and that’s not helping our students because they’re not learning professional communications when we do that.

Kevin Patton: Not only that, there are some students who really have a hard time with just the language. Not just the English language, but just reading in general. For example, students that have dyslexia or some similar issue with the way they read language and so on, and things like typos, improperly formatted terms and so on can really confuse them. Now, that doesn’t normally confuse me. At least not usually, because I can kind of see through that, but then again, I don’t deal with dyslexia, so for me, that’s not a big deal, but there are a lot of students who have those kinds of issues, and again, we don’t want to mess them up.

Kevin Patton: Besides that, we want to be a good model for professional communication. Now, some of the benefits of using this list are, and I think this is the biggest one, is when we use a dissection list that says, “Here is what you need to know exactly”, “Here is what you need to know for the lab practical”, then we are being as clear as clear can be on what they need to know. Isn’t that really helpful to students when we’re as clear as we can possibly be to let them know, “This is it. This is the beginning and end of what you need to know”? Even if what we put on our list is just a listing of all the boldface terms in our lab manual or atlas or handout or whatever we’re using, if you just tell them, “Well, you need to know all the boldface terms that are in the lab manual in this section of the lab manual”, okay, that might work okay, but a lot of students, they’re not really going to …

Kevin Patton: It’s not going to pop out to them, and they’re going to miss some. Remember, there are some students that might not be able to really see the boldface type as boldly as you’re seeing it, but besides that, it’s just kind of messy, and I think by taking the information, yes, they already have it in one form, and yes, they ought to be able to translate that into their own list. Sometimes, just giving them the list makes it more concrete for them, and it’s more of a guidance for them, and it’s more helpful to them. That being said, if there is time available or you want to take this approach for whatever reason, maybe you could make a pre-lab assignment to be, you make your own list of all the boldface terms, and then we’ll check each other’s lists when we come into lab to make sure that none are missing, but there is always that danger of something being missing and a student not studying what they need to study for the test, and maybe that’s on us when that happens if we haven’t really ensured that they have the correct and complete list. Another advantage of using a dissection list is it gives them a tool to use during the dissection. That is, it becomes one of their dissection tools and it allows them to progress in an orderly way because remember, they’re checking it off, okay?

Kevin Patton: “I know I found this. I’ve now, I’ve found this one. Now, I’ve found this one” and so on, and so it’s a tool to keep progress, and it also helps you. It’s a tool for you as the teacher to see how they’re progressing, because you can’t keep your eyes on each student all the time to see if they’re really doing everything, if they’re really progressing, and so that becomes a tool to kind of help fill in the blanks as you move from student to student or lab group to lab group and so on to, if they have them have their dissection lists out and look at how they’re checking it off and ask them questions about that. “Did you really find all of those already this quickly, or are you just checking things off?”

Kevin Patton: Not in an accusatory way, but in a way that’s kind of saying, “I know how this game is played, and we don’t want to play that game because you’re not going to learn anything.” Use your time now in lab, and I’m going to help you do that, so let’s sit down and let’s go through these. It’s a tool for you as the teacher, and I think another benefit is it supports their confidence level. It’s sort of like having training wheels on the bike, where they might not really absolutely need those training wheels, but it gives them a certain level of confidence so they can jump into it and really get moving without hesitating too much. Again, this was never a problem with me with dissection.

Featured topic 2: Pre-dissection practice

Kevin Patton: I always just charged in there because I enjoyed it so much as a student, but some students are much more hesitant, either because of lack of confidence or in their abilities or in their lack of confidence in their comfort level with doing dissections, especially if they’re new at dissection, so this is a tool to help them. It gives them somewhat of a level of confidence to start off with. It’s a map that they have alongside them to help them along. The question I have for you now is, “Have you used dissection lists like this before, and if so, what did you find useful?” Maybe there was some problem that you ran into.

Kevin Patton: What are those? I want to hear about that. We all want to hear about that. We want to hear about your ideas for the best use of dissection list, or if you have some ideas about why it’s not a good idea to use a dissection list, we want to hear that too.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association of Anatomists at Anatomy.org.

Kevin Patton: As I’ve said before, the dissection activity that we do in the undergraduate A&P lab course can either be a big, messy, free-for-all where the students really aren’t learning much, or it can be a more focused activity where the students really are learning more deeply and more thoroughly in getting a better appreciation for the structures of a particular organ or of the whole body. One of the ways that I’ve found that makes things go in that better path, that is the path of a focused activity where the time is really well-spent and the learning is very deep, is to do a pre-dissection activity, which is basically a low-tech virtual practice dissection that the students do before they do the real dissection. The way I do that is sort of an application of a strategy that I mentioned just very briefly way back in episode 10, which was entitled 9 Super Strategies for Teaching the Skeleton. I mentioned that I might print out a skeleton, or I might print out a set of bones and have students find the structures there before they actually get into the lab so that they’ve had a little bit of practice with it before they’re looking for it on the skeleton so that their time is better spent in that limited lab time that they have with the specimens. The same thing is true for dissections of like a sheep brain, or a sheep heart, or a mammalian eye, or spinal cord, or any of the other many kinds of dissections that we might be doing in the undergraduate A&P lab.

Kevin Patton: For example, let’s use the sheep brain as an example. What I will do is give them a handout ahead of time that has photographs of the sheep brain on a sheet of paper. Sometimes I use those really big sheets. They’re like a double of a standard sheet of a copy paper, so they’re the 11 by 17, rather than eight and a half by 11, but I’ve done this with a regular eight and half by 11, and I’ve printed it out in color. I had our copy center do that, but I’ve also done it in black and white, and to be honest with you, I think the color looks prettier.

Kevin Patton: I think it’s really cool, but I think the black and white works just as well, so why not use that, and you don’t feel so bad for spending so much money on all that toner and so on, and sometimes depending on the copy machine itself on the color copies, the toner actually has kind of a waxy sheen, so it’s kind of hard to write across, to draw lines across it and so on. What I do is I go online and I find copyright free images of sheep brain cut in different ways. There’s lots of those because everybody in the world dissect sheep brains and lots of students take pictures and post them, but you need to find some that you have permission to use. Might be in public domain or Creative Commons license or something like that, or even better, what I’ll do sometimes is just get my phone out and take some pictures of the sheep brain from different angles and maybe cut along different planes. Then, I take those images and I put them in Microsoft Word and start arranging them on the page, and there are some formatting tools in there where I can actually remove the background very easily, so it’s just the sheep brain specimen, and not all the junk behind it or next to it, and I’ll arrange those and I won’t label them.

Kevin Patton: I give that as a handout to the students, and I tell them, “Before you come, you need to walk in the door here having already gone through our lab directions for dissecting the sheep brain, and I want you to find this list of structures”, so I give them their dissection list. “This is your list of structures, and you need to find them and label them on this sheet.” Depending on the specimen, there might be more than one sheet. I give them like maybe two or three pages of let’s say the sheep brain cut on different angles, so on, and so they need to go find it there and label it. I tell them that if they can’t find it, they’re really stuck, then write the name on the sheet and just put a question mark by it so that I know that you’ve looked for it, so when they come in and they start getting their materials together and getting organized, I start walking around and say, “Well, do you have your practice dissection?”, and have them get it out, and if they don’t have it, we can have a talk about that, why that’s important that they needed to have had that, and if they do have it, then I can go through it and say, “Well, and you only found five things here, but I have 25 things or 55 things or whatever on your dissection list. Let’s talk about that”, and so that’s a good teaching moment.

Kevin Patton: It’s a good coaching moment when those kinds of things happen, and they will, and they do happen. Then, of course the next time you do a dissection, they’re much more likely to have it done because they know you’re going to have a little coaching session with them if they don’t have it done. What I’ve found is the students feel a lot more confident when they come in. They feel like they know what they’re looking for. Whereas before I started doing that, the students would often just express to me bluntly and say, “I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing here.”

Kevin Patton: “I don’t know what I’m supposed to be seeing. I don’t know how I’m supposed to do this”, but if they’ve done it in a practice mode in this very low-tech practice mode where what they’ve done is labeled photographs of dissected specimens, then they know what they’re looking for. Then, when they see it in 3D, I think they’re going to appreciate the dissection experience that much more because it’s going to pop out. It’s no longer 2D. It’s now 3D, and they can move it around, and they can identify textures, and they can bend the things around or poke through them or cut through them and so on and look at different things than they were able to do with just the photograph.

Kevin Patton: Try it and see if it works. It has worked really well for me. If you have some ideas on how to make it better or some alternate ways of doing that, or of some other activity that this reminds you of that you want to share with other listeners of this podcast, please contact me on the podcast hotline, or by email, or twitter or whatever.

Aileen: The A&P Professor is hosted by Kevin Patton, professor, blogger and textbook author in Human Anatomy and Physiology.

Kevin Patton: This episode is dedicated to the memory of Sister Virginia Brinks, who mentored me as her apprentice in teaching A&P for five exhilarating years.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is with the free mobile app:

Or you can listen in your favorite podcast or radio app.

Click here to be notified by blog post when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free:

1·833·LION·DEN

(1·833·546·6336)

Local:

1·636·486·4185

Email:

podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

![]() Please click the orange share button at the bottom left corner of the screen to share this page!

Please click the orange share button at the bottom left corner of the screen to share this page!

Preview of Episode 35

Introduction

Kevin Patton: Hi there. This is Kevin Patton with a brief audio introduction to episode number 35 of The A&P Professor podcast. Also known as TAPP radio, an audio happening for teachers of human anatomy and physiology and related courses.

Topics

Kevin Patton: In episode 35 I have some news about how smell relates to stress and some news about how oxytocin works and I’m going to discuss something about the value of cholesterol testing for cardiovascular risk. And the featured topic is: big ideas. That is the essential concepts of A&P.

Word Dissections

Kevin Patton: Well, it’s time once again for word dissections and unbelievably the first word we’re going to dissect this time is “dissection”. That is the word “dissection.” I’m going to start off with asking a question about its pronunciation. You know how I pronounce it, dissection, but a lot of people pronounce it as die-section. And I’m going to swing back around to that question in a minute, but first let us do our dissection. The first word part is “dis”, D-I-S and that means “a part”. The second word part is S-E-C-T or sect, and that means “cut”. Then of course, the last part “shun” means “a process”. So, you put that all together, dissection is a process of cutting apart, which makes sense, right? ‘Cause that’s what we do when we dissect. We cut things apart.

Kevin Patton: Coming back around to that question how do you pronounce it, I think there’s a really strong case to be made that the correct pronunciation of that word is dissection, because the first word part is “dis” not “dice” or even “die”. Now, there is a work part that we could use in some terms that is di, D-I. It could mean “two”, for example, but that’s not the word part we’re using here. The word part we’re using there. The word part we’re using here is “dis” and we don’t normally pronounce that as “dice”, so it makes sense that dissection would be the correct pronunciation. However, as we’ve discussed in previous episodes, you know sometimes what starts out as a mispronunciation or a misunderstanding based pronunciation, become part of the main stream. I think we can say that dissection is correct on that basis, that is that it was become part of the mainstream. So, I wouldn’t say it’s incorrect to say dissection, but I think there’s a stronger case for pronouncing it dissection.

Kevin Patton: Now, something else related to this term that I wanted to bring up is that in the previous episode, episode 34, we talked about ways that we could make dissections activities in our class work a little better. And in that discussion, I was discussing planes of the body, like midsagittal plane for example, and sections such as a midsagittal section. And I discovered that when I was doing my editing, that I swapped them. I wasn’t using them correctly. And I think I fixed it in the editing, so if it sounds a little funny, when you’re listening to that section, because I had to drop in planes where there was section and section where there was planes, because a plane is something that is imaginary. It’s sort of an imaginary flat surface that we can imagine is cutting a sheep brain for example in half one way or the other or in third, or wherever it is … on an oblique and it could be an oblique plane.

Kevin Patton: So, a plane is sort of like what direction we’re cutting in. The section is that cut itself, and I had swapped them and I said that I was cutting a midsagittal plane or something like that. I don’t remember exactly what I was saying, but I cut along a place, but I’m cutting a section. I’m making a section, let’s put it that way, ’cause that’s kind of redundant to say cut a section. I’m cutting a cut. But my point is that we do need to be careful about how we use planes and sections, and I thought I was being careful, but when I looked back, I wasn’t. So, let’s try to analyze the way we’re talking about it in our classes. ‘Cause you can’t go back and fix it in audio editing when you’re in a live class. I guess you can in a flip class, but not in a live class.

Kevin Patton: Another word part or another word that I want to dissect is the word “concept” Which we’ll be using a lot in the full episode coming up here. So, concept starts with the word part “con”, C-O-N, and that means “with”. And then the second part of the word is “cept”, C-E-P-T, and that is really a shortened form of a Latin word which is ceptus, and that refers to something seized or taken or brought along. So, when we put “con” together with “cept”, we’re putting together things we’ve taken. And so that fits in with the actually working definition that we use in English for “concept” and that is it’s an idea of something. It’s formed by combining all the facts that you know about it. So, we’re seizing or taking those facts and putting them together with each other. So, concept.

Kevin Patton: Our third and last word that we’re going to dissect is “gradient”, which I’m also going to be talking about in the next episode and we’re all familiar with that term. We use it a lot in our explanations at A&P, don’t we? And yet even though it’s an ordinary English word as was the word concept, we can still break it apart into its word parts and that can kind of help us understand better what it is. So, in “gradient” the first part is “grad”, G-R-A-D and that literally means “to walk” or “take a step”. So, grade often refers to things that are stepwise. After grade comes “I”, the letter I and that doesn’t mean anything. That’s just a combining vowel. And then the last word part is “ent”, E-N-T, which means “a state”. So, gradient is a state of something being stepwise.

Kevin Patton: So, for example, when we talk about a concentration gradient, we mean that at one end of our scenario the concentration is at one value and then it either increases or decreases stepwise as you get toward the other end of that scenario. Or we could talk about a pressure gradient and say that the pressure is one value at this end of the situation and it’s a different value at the other end of the situation. And it graduates, that is it increases or decreases in a stepwise fashion as we move from one end to the other. So, gradient. It’s a stepwise state of concentration or a stepwise state of pressure, or of light, or of color, or almost anything, right? That can be graded.

Kevin Patton: Oh, wait. I forgot one. I said gradient was the last one. But I have one more. So, we’re just going to call this one a bonus word dissection, okay? It’s probably the most complex one. So, it’s a double bonus word dissection. And the word is apolipoprotein B. Yeah, that’s right. Say that ten times real fast. Apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein B, okay. I’m not going to do that. So, let’s break it apart. “Apo”, the first part means “away” or “off of” or “apart”. And then the second part “lipo” L-I-P-O, means “fat” literally. And then the last part … well, we can take two parts together and call that “protein”, but “protein” in turn is made up of two word parts, the “prote” part, which means “first order” or “primary” and then the second part is I-N, the I-N ending, which just is an ending that refers to a substance. So, “protein” is a “first order or primary substance.” That’s what that literally means.

Kevin Patton: So, a lipoprotein is a molecule that is a combination of a lipid and a protein or lipids and proteins. And we know that lipids and proteins form particles of various sizes that float around in our bloodstream that include cholesterol and when you take the protein part away, or consider it separately, then that’s where the apo part comes in. That is, an apolipoprotein is the protein part of that lipoprotein. And so, that’s what an apolipoprotein is, but what about that B hanging off there at the end? Well, B refers to the fact that it’s in the B class of apolipoproteins. There are actually seven classes that have been identified. They are A, B, C, D, E, H, and L. So, apolipoprotein B is from the B class of apolipoproteins.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton: This preview podcast is sponsored by HAPS, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S.

Elaine Marieb

Kevin Patton: Elaine Marieb, retired A&P professor and author of several popular A&P textbooks and lab manuals once said, “Education gave me the faith and confidence I have in myself and I would love to help instill that faith in students pursing careers in health professions. Be diligent in your studies, because only when you are can you gain the sense of accomplishment that brings confidence in yourself. With confidence and education you can change your life.”

Kevin Patton: Elaine was one of the first people I met at my first HAPS meeting and we continued to have brief chats over the years, mostly as we sat together as early arrivals waiting for the venue to open before the annual banquet at each HAPS Conference. Drink ticket in hand. She always seemed to have some powerful and often wickedly funny bit of advice for me about the business of writing textbooks. I’m sad to say that Elaine Marieb died on December 20th of 2018 in Naples, Florida at the age of 82. Cheers, Elaine!

Book Club

Kevin Patton: Well, I have another recommendation from the A&P Professor Book Club. This one is a book I’m going to talk a little more about in the full episode, but here’s a little preview here. It’s titled “The Core Concepts of Physiology: A New Paradigm for Teaching Physiology” and it’s put together by a group of people headed up by Joel Michael, William Cliff, Jenny McFarland, Harold Modell, and Ann Wright. It’s published on behalf of APS, the American Physiological Society by Springer, which is a major publisher.

Kevin Patton: I have links in the show notes, and at the episode page where you can acquire this book, but I want to clarify that a little bit. One of the links I give you is to a page at the American Physiological Society website and if you are a member and you’re logged in as a member of APS, you can download this book for free. The other link that I give you is to Amazon where you can purchase the hard copy of the book. And looking at the recent price on Amazon of the book, if you’re not a member of APS, it might be worth joining just to get this book, because depending on what level of membership you join at, it’s close to being a wash if you do that.

Kevin Patton: So, you get the book and the membership and the membership is very valuable. I’ve been a member of APS for a long, long time and I get a lot of value out of it. Not only from the physiological journals that they publish and information coming out of their various meeting and the networking that I’m able to do, but they have a journal called Advances in Physiological Education, which is fantastic. And it’s go a lot of information in there about some of the various teaching principles that we’ve talked about on the podcast and many more. And a lot of studies showing how they can be applied and what works best and just all kinds of ideas. And it’s not strictly physiology. There’s a lot of information in there about the A&P course as well. So, it’s worth checking into.

Kevin Patton: But getting back to this book. This book came out of a project where they were looking at this whole ideas of the basic concepts of biology and they took it in the direction of human physiology. And they sort of boiled everything down into 15 core concepts and they include things like evolution, homeostasis, causality, energy, and so on. I get into those a little bit more in the full episode, but you can look in the show notes. I have them listed there as well. And then it goes into how that approach to teaching physiology or in our cases we’re teaching mostly anatomy and physiology combined, it can be applied that way as well. It really is a very interesting and useful take on how we approach the whole story of the human body, of structure and function of the human body. So, it’s really recommended that you at least read parts of that book to kind of see that idea that they’re going through and it’s very well done. So, I think that you’re really going to enjoy going through it.

Kevin Patton: A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this preview episode are funded by AAA, the American Association of Anatomists at anatomy.org.

Kevin Patton: Well, this is Kevin Patton signing off until our next episode and reminding you to keep your questions and comments coming. Why not call the podcast hotline right now at 1-833-LION-DEN? That’s 1-833-546-6336 or visit us at theAPprofessor.org. See you next time.

Last updated: September 15, 2021 at 21:39 pm